Machine Teaching Requires Behaviorist Approach by Thomas Ultican

The controversial Harvard psychology professor B. F. Skinner (the B. F. stands for Burrhus Frederic) taught pigeons to play ping pong, created a box for tending babies more efficiently called an air crib and became the national mouthpiece for behaviorism. His predecessor in behaviorist theory was Columbia University Psychology Professor Edward Thorndike. In 1898, Thorndike published the law of effect which posited that responses which produce a satisfying effect are more likely to occur again and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to repeat. Skinner developed an enhancement of this learning theory that he called operant conditioning.

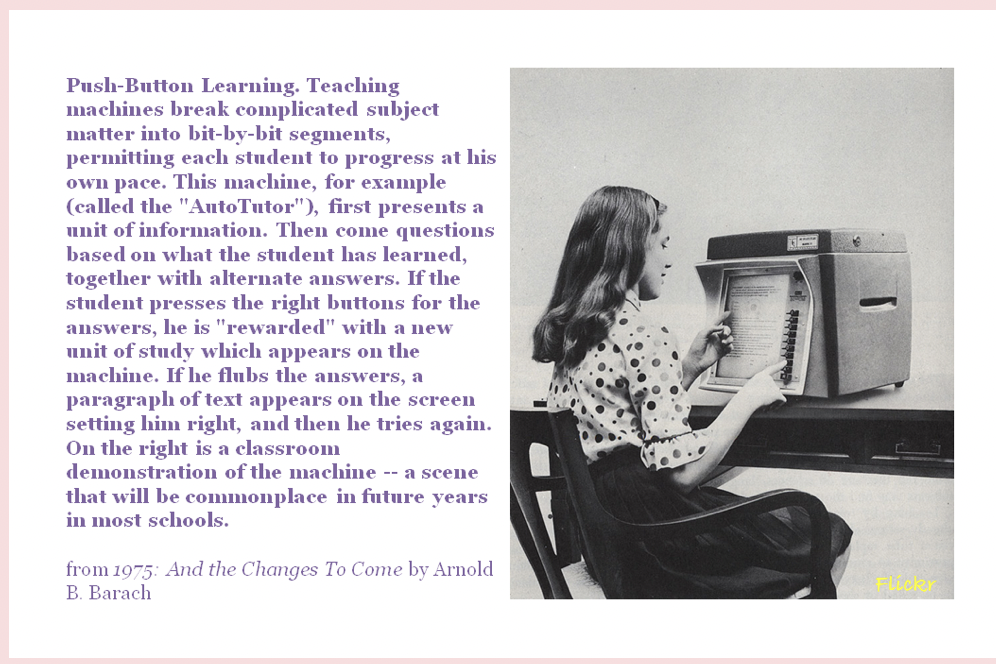

Operant conditioning, sometimes referred to as instrumental conditioning, is a method of learning that occurs through rewards and punishments. Skinner believed he could create a machine that would reward students as soon as they got a correct answer and send them for more instruction if they missed an answer. By using “programmed instruction” which broke learning into small chunks, Skinner claimed students would be able to interface with his machines and at a “personalized” rate learn more deeply and efficiently.

The story of these machines and their promises of enhanced learning is chronicled by the amazing Audrey Watters. She has added significantly to the history of mechanized teaching, the philosophical basis supporting it and how it relates to the modern computerized version. Her new book, Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning published by MIT press is wonderfully sourced. In it, Watters states,

“What today’s technology-oriented education reformers claim is a new idea – ‘personalize learning’ – that was unattainable if not unimaginable until recent advances in computing and data analysis has actually been the goal of technology-oriented education reformers for almost a century. Education psychologists like Sidney Pressey, the person often credited with inventing the first ‘teaching machine,’ talked about using mechanical devices in the 1920s in ways almost identical to those who push for personalized learning today. All so that, as Pressey put it, a teacher could focus on her ‘real function’ in the classroom: ‘inspirational and thought-stimulating activities,’ including giving each student individualized attention.” (Teaching Machines page 9)

Audrey Watters has been writing about technology in education for most of the 21st century. She published The Curse of the Monsters of Education Technologyin 2016 and based on the research for that book, she made these remarks to a class at MIT.

“I don’t believe we live in a world in which technology is changing faster than it’s ever changed before. I don’t believe we live in a world where people adopt new technologies more rapidly than they’ve done so in the past. … But I do believe we live in an age where technology companies are some of the most powerful corporations in the world, where they are a major influence – and not necessarily in a positive way – on democracy and democratic institutions. (School is one of those institutions. Ideally.) These companies, along with the PR that supports them, sell us products for the future and just as importantly weave stories about the future.”

Will Teaching Machines Replace Teachers?

In 1954, Skinner was provided space at Harvard where he assembled a team of “bright young behaviorists” including Susan Meyer (Markle). They “started work on designing their new teaching machines as well as ‘programs,’ the material that would accompany them.” (Teaching Machines page 135) This led to “programmed instruction.” Watters explained,

“Programmed instruction was individualized instruction. Meyer Markle likened it to the work of a tutor, ‘a master of intellectual teasing’ who adjusts the lesson to her student’s needs but also challenges the student to keep moving forward. … ‘Each student was now to have his own private tutor, encased in a small box.’” (Teaching Machines pages 138 and 139)

According to Watters, Meyer Markle was the most significant contributor to the development of programmed instruction but in the 1950s women like her were professionally undermined and men were normally credited instead. Watters identifies Norman Crowder as the most likely to be credited with innovations in programmed instruction instead of Meyer Markle.

In 1958, Doubleday started publishing Crowder’s series of self-instruction manuals – “TutorTexts.” An ad in Popular Science said TutorText was “a complete programmed teaching machine in book form.” (Teaching Machines pages 139 and 140)

In 1959, Crowder claimed, “Automatic tutoring by intrinsic programming is an individually used, instructorless model of teaching which represents an automation of the classical process of individual tutor.” Watters notes, “While Skinner and Pressey were quick to insist that their teaching machines would not replace teachers, Crowder clearly felt less obligated to do so.” (Teaching Machines page 142)

Many people were giddy about the possibility of replacing teachers with these marvelous new machines. The machines were believed to be creating new markets while improving education. Caution was thrown to the wind. Pressey wrote,

“I was shocked at what followed: the most extraordinary commercialization of a new idea in American education history -…. Then millions of research dollars went into, first, the confident elaboration of these ideas and only slowly into any questioning of them.” (Teaching Machines page 148)

The same greed blinded path has been followed by the promoters of digital education. They continue to over-promise while hyping untested behaviorist based learning at a screen. It is more mindless implementation without questioning.

“Banking model of education”

In Teaching Machines, Watters illuminates the history of promoters like Skinner completely forgetting scholarly caution and diving headlong into achieving lucrative manufacturing deals with corporations like IBM, Rheem and Harcourt Brace. At the same time, door to door encyclopedia salesmen began selling books by Crowder and others that implemented programmed instruction. The parallels with today become obvious.

There is a big difference from the teaching machine era (1928-1980) and today. Then, large technology corporations were not nearly as powerful which meant voices of education professionals started to be heard and the mania subsided.

The Brazilian educator Paulo Freire famous for being jailed by the 1964 Brazilian coup leaders called machine learning the “banking model of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing and storing the deposits.” He contrasted that with “problem posing education,” which is a dialogue between teachers and students in which knowledge is jointly constructed. (Teaching Machines page 226)

Even the father of teaching machines, Sydney Pressey soured on behaviorism. Drawing on the work of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, “Pressey challenged behaviorism for failing to adequately account for the developmental stages children pass through – and pass through without ‘so crude and rote process as the accretion of bit learning stuck on by reinforcements.” He felt the teaching machine movement faced a crisis because of behaviorism. (Teaching Machines page 234)

Noam Chomsky reviewed Skinner’s book Beyond Freedom and Dignity for the New York Review of Books in 1971. In his article “The Case Against B. F. Skinner” he wrote, “Skinner’s science of human behavior, being quite vacuous, is as congenial to the libertarian as to the fascist.” (Teaching Machines pages 239 and 240)

This is just a short taste of the content of Teaching Machines. It is a special book by a special writer.